“I try to create relationships in the paintings that are odd enough to not have a good explanation. And usually, if you put enough things together that don’t have a good explanation, then people will create their own. That is what I am trying most to do.”

For over four decades, Chicago-based artist Jim Lutes has produced a varied yet unmistakable body of work that explores the specific tensions between figuration and painterly abstraction. Often discussed in the context of Chicago Imagism, Lutes’s distinct style draws from an expansive set of art historical sources that blend elements of West Coast Funk, Abstract Expressionism, and postmodern appropriation. Gritty urban street scenes, stills from television and darkly comic self-portraits intermingle with calligraphic paint strokes, cartoon-like blobs and bulbous forms in Lutes’s compositions. The dynamic range of subjects to which Lutes has lent his deep painting vocabulary has prompted curators to feature his work in seminal exhibitions such as the 1987 and 2010 Whitney Biennials and documenta IX in 1992.

“The duality between figurative or representational and abstract, to me, has always been a false dichotomy because both of those aesthetics reside quite comfortably in tandem in my head.”

Jim Lutes, Between the Falls, 2020

Lutes worked exclusively with oils until the late 1980’s, when he adopted the use of acrylics hand-mixed from dry pigment as his preferred medium. Invigorated by the spontaneity he could achieve in acrylics, specifically the tension in pictorial space of the figure-ground relationship, Lutes pursued further experimentation in his own unique combinations of multiple painting mediums. It was around 2000 that Lutes landed on what is now his preferred material: egg tempera. Used on its own or in suspensions of egg and oil, Lutes wields this famously challenging painting medium as a master. Skeins of ribbony marks range in saturation to both reveal and obscure the subject. Curator Hamza Walker finds this duality especially captivating. Walker views the artist’s ethereal surfaces with the question, “Where, when, and how do they begin or end?”[i]

Art historian Barry Blinderman elaborates on this technique: “There is a climax-defying irreconcilability to Lutes’s work. While the thin glazes of the egg tempera technique allow the viewer to peer into the paintings’ guts... the logic through which his trademark squiggles and swirls cohabitate anxiously with the underlying images remains oblique, even impenetrable. How can near-transparency be honed to such exquisite opacity?"[ii]

“My exploration with materials was essential to working improvisationally. It was through the things I would see in the puddles or shapes or things that I would paint that I would get my idea. In the same way that we look at the clouds and see things, I can’t look at anything without starting to organize it in my head.”

Mark Tobey, Festival, 1953. Seattle Art Museum.

Lutes’s work emerges from a career-long amble between abstract and figural painting deeply influenced by both his mentors and by earlier artists of the twentieth-century. During his BFA studies at Washington State University in Pullman, where he studied under the tutelage of various mentors including noted Pacific Northwest artist Gaylen Hansen, Lutes was introduced to the pioneering work of Mark Tobey.

Tobey’s style of “white writing”—in which he overlaid abstract fields with light-colored calligraphic symbols—helped spur Lutes’s use of calligraphy in his paintings. Indeed, Lutes often uses swirling calligraphic gestures as the seed of each work, wrestling with recognizability and obfuscation as he improvises each composition.

As the artist states, “I am always looking for something. Although, I am comfortable not knowing what it is. I try to sustain that period of not knowing until the painting becomes rich and has bypassed the places I’ve been before.”

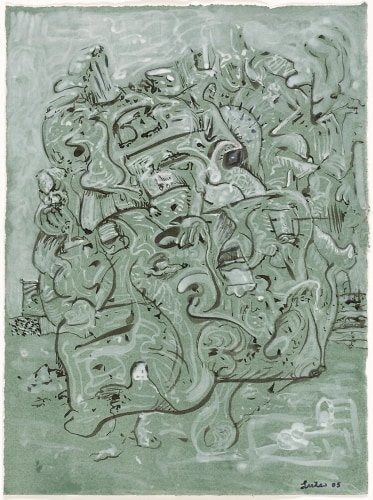

Jim Lutes, Untitled, 2005. Art Institute of Chicago.

Willem de Kooning, an impactful figure in the history of Post-war painting who veered between abstraction and figuration, has also deeply influenced Lutes’s career. In examining that influence, curator Debra Bricken Balken notes the painters’ mutual faith that “an artist’s practice should be able to accommodate multiple interests, such as conjoining the body with an abstract field.”[iii]

Lutes’s oeuvre stands alone in the manner in which it amalgamates art history while incessantly transgressing it, pulling together the clashing registers of high and low visual culture which he first witnessed on the pages of popular magazines.

He became absorbed with these assumed values and with the duality of representation and abstraction, noting that “usually, when a painting is missing something and it doesn’t have both of those elements to some extent, it’s probably because one element is not challenging the other one. It’s that opposition and that dichotomy that I am most interested in.” This refusal to follow either pole of painting led Lutes toward transgressing even more in the materials he worked with, down to his very technique of mixing paint.

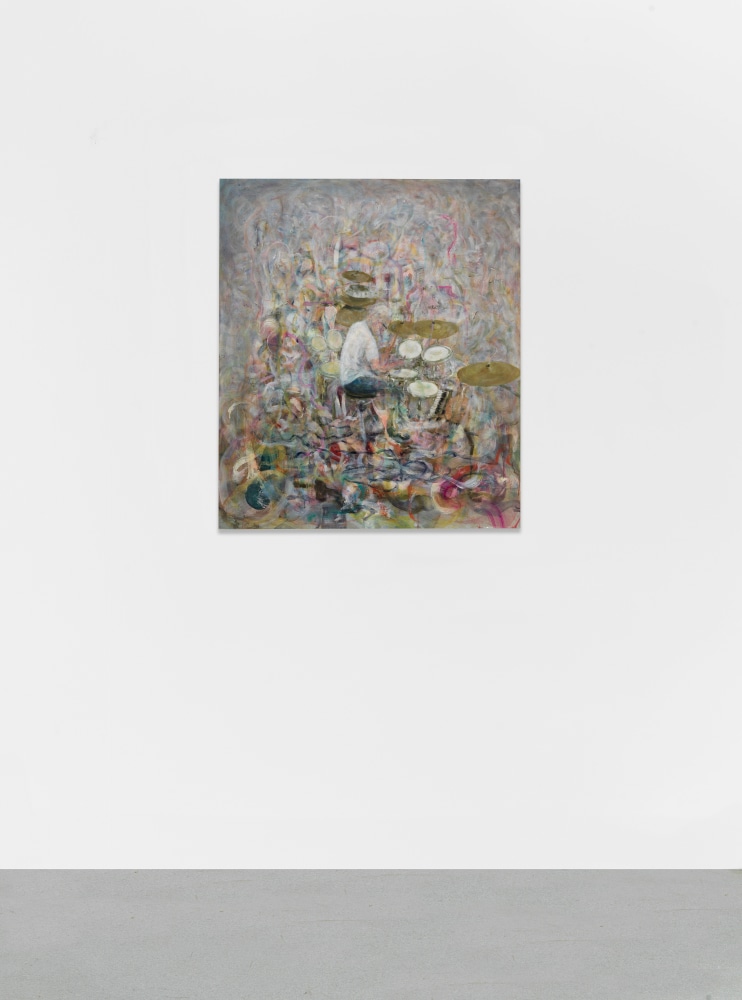

Jim Lutes, No Solo, 2020.

NO SOLO, 2020

Music is also a central influence in Lutes’s practice. A drummer since high school, Lutes has performed for years as a percussionist in the jazz-noise quartet Tiny Hairs. Writing on the artist, art historian Barry Blinderman considers Lutes’s fluid dexterity with paintbrushes and drumsticks alike:

There’s an undeniably poetic parallel between hitting skins stretched over wooden cans and applying marks to a canvas stretched over a wooden framework. The drummer sits before a sprawling, multipartite contraption and pounds out rhythms in various timbres. The painter uses equally archaic equipment to mark time in a messier way. Perhaps because of this, the boundary between Lutes’ music and his painting is delightfully porous.[iv]

This interchangeability of visual and acoustic instruments can be confirmed in the artist’s studio, where a drum set is never far from the equally rhythmic canvases on his easel. In his essay accompanying the painter’s Renaissance Society retrospective, Walker writes, “Just as [Lutes’s] work literally speaks of his immediate surroundings, be they studio or living room, home or street, his work also speaks of the world’s place in him.”[v]

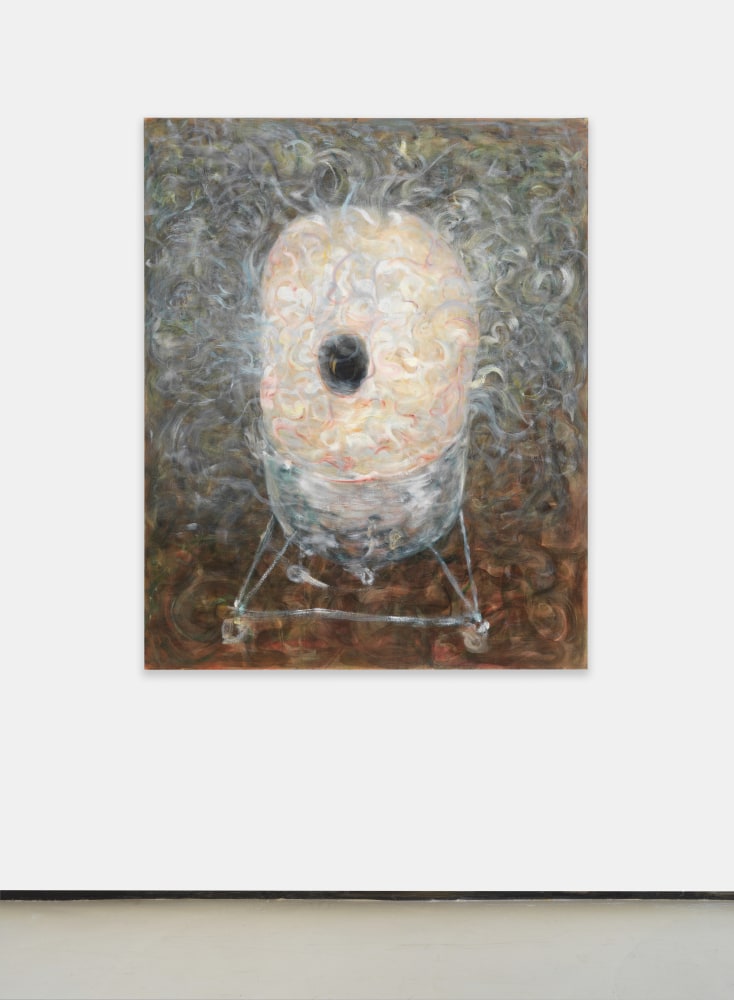

Jim Lutes, Smoking Hole, 2010-19.

SMOKING HOLE, 2010-2019

More often than not, Lutes leaves traces of his surroundings in unfamiliar forms, guarded by a veil of swirling strokes. With some canvases, like Smoking Hole, 2010-2019, Lutes returns to the composition over the course of many years, embracing his shapeshifting process of drawing figures partially out from behind the haze of tempera marks:

"My paintings often evolve over a number of years. It’s not by plan and it’s not because they take that long to make. It’s because I get them to a point that they are almost finished — but almost is the key word there. I have to accept, given the way that I work, that if I am going to go back into a painting, it has to be able to become anything."

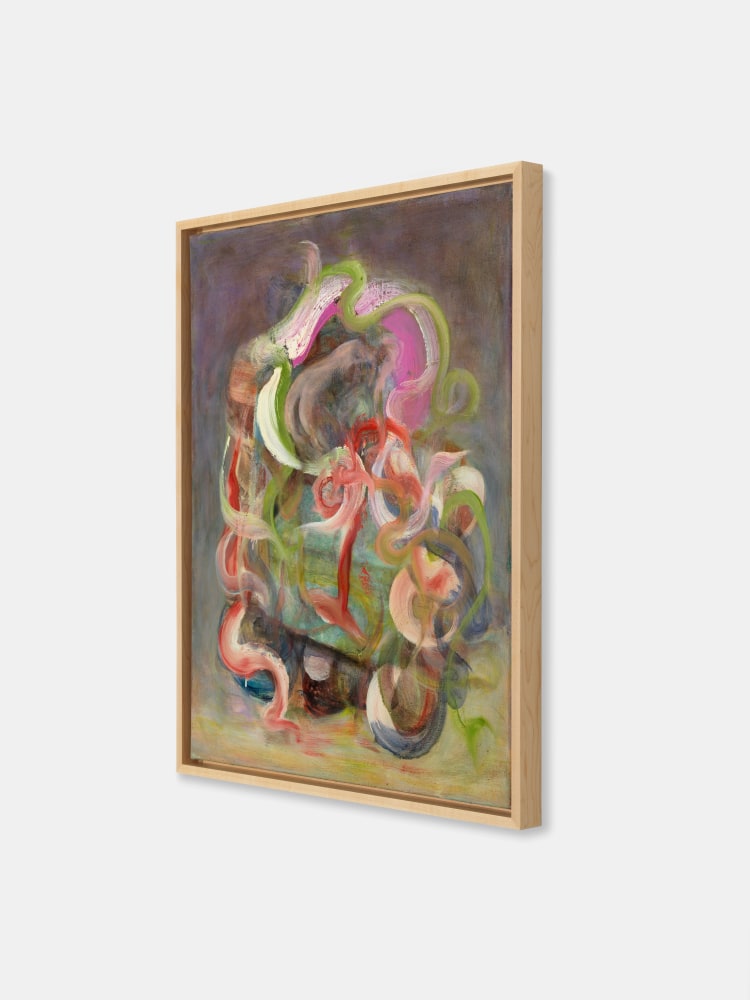

Jim Lutes, Hassock Assock, 2020.

HASSOCK ASSOCK, 2020

Lutes’s insistence on avoiding the certainty of a preconceived image or endpoint gives him both freedom and a challenge. By leaving the compositions still seemingly in formation, still at the cusp of recognizability, Lutes opens the door to both his studio and his improvisational process:

"If you look at my paintings in a rational or linguistic way of thinking about art, you won’t see any image, it won’t appear. You’ll see the relationship between all the marks and the colors and the fields and the texture, and I try to put enough there to entertain one on that level without allowing it to get to the point where someone could interpret the painting based on that information. But if one were to look at the painting and allow their mind to wander or allow their gaze to become more generalized and less specific, images would begin to appear or go away, and other images reoccur."

BIOGRAPHY

Jim Lutes was born in 1955 in Fort Lewis, Washington. In 1974, Lutes began his formal study of art at Washington State University in Pullman, where he would receive his BFA under the tutelage of noted Pacific Northwest artist Gaylen Hansen. Lutes left Pullman in 1980 to pursue an MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Lutes’s eclectic and increasingly identifiable style earned him several key opportunities to exhibit in the States and abroad, including the 1985 and 1993 Corcoran Biennials, the 1987 Whitney Biennial and documenta IX in 1992. His contributions to the discourse of painting were again recognized by the Whitney in the 2010 Biennial.

Lutes’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions and museum retrospectives at Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (1994); Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent, Belgium (1995) and The Renaissance Society, University of Chicago (2009). His work can be found in significant institutional and public collections such as the Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; De Paul University Art Museum, Chicago; Phoenix Art Museum; SMAK-Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent; and the University of Chicago, among others. Lutes lives and works in Chicago.

i. Hamza Walker, “Painter on the Make,” Jim Lutes (Chicago: The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, 2009), 13.

ii. Barry Blinderman, “Grooving in Analog (What the Paintings Sound Like),” in Jim Lutes: Paintings and Drawings 1995-2008 (Normal, Illinois: University Galleries of Illinois State University, 2009), 13.

iii. Debra Bricker Balken, “Jim Lutes: Recent Paintings,” in Jim Lutes: Half-Ass Rapture (Chicago: Valerie Carberry Gallery, 2009), 3.

iv. Blinderman, 14.

v. Walker, 13.