GRAY presents the work of American artist Evelyn Statsinger (1927-2016) in the solo exhibition Currents.

Organized with writer and curator Dan Nadel, Currents presents Statsinger’s paintings and drawings from the 1980s and 90s, a period in which she developed her most immersive and otherworldly compositions.

“[For] fifteen years, I have intently watched [the] daily life of plants and animals in both the forests and the fields… Bits and pieces of specially observed things begin to represent the whole, and juxtapositions of real things make imaginary combinations. Combinations are open and ambiguous to interpretation, so that the viewer may wander in the same state of grace as the painter.”

– Evelyn Statsinger

Tides

By Dan Nadel

Bare autumnal tree, Allegan, MI, 1982

In 1991 Evelyn Statsinger was asked for a statement on the painting Random Paths, 1989, and she wrote:

This work was completed in my studio in Allegan, Michigan, a place where for fifteen years I have intently watched [from spring through fall] the daily life of plants and animals in both the forests and the fields.

The title refers specifically to random walks on random paths. [sic] It is also, however, a metaphor for the life of the mind, a kind of strolling through the actual present landscape, as well as remembered landscapes. Bits and pieces of specially observed things begin to represent the whole, and juxtapositions of real things make imaginary combinations. Combinations are open and ambiguous to interpretation, so that the viewer may wander in the same state of grace as the painter.[i]

View of the artist's garden, Allegan, Michigan, 1980

The same could be said for much of the work in this exhibition and catalogue—all of it from a time when the artist had immersed herself in the dunes, woods, and shrublands of Allegan, Michigan, the town to which she would decamp from April to October, living in an 1890s schoolhouse that she shared with her husband Stanley Cohen. When Statsinger would return to their prewar apartment in downtown Chicago, she imported the outdoors to the city by bringing with her those specially observed bits of matter and setting them on her mantel.

The artist in her garden, Allegan, Michigan, 1980

Twenty-five years later, in a guarded interview with the Archives of American Art, she reflected again on her time and space in Allegan, which by then had grown to nearly thirty or forty acres of land:

[We were] just going to use it for weekends, but I couldn’t—the spring is so beautiful, and the fall is so beautiful. Now we use it for about five months of the year. And it made a really big difference because it’s the first time—we built a pine forest because part of it is a moving dune. . . . And I had bare roots in little cans, and I told everybody we’re building this pine forest, and now it’s enormous. . . . [In nature] I can experience seeing the different seasons and how things change from one thing to another [and] that I’ve just seen those things, which I had never seen before.[ii]

Statsinger also mentions that this area was all dune land at one time, and that it was all Lake Michigan, and that it still has “diatomaceous earth around and so forth.” Diatomaceous earth, a term Statsinger deploys so casually that she might’ve invented it, is a sedimentary rock composed of the fossilized remains of algae. Relatively soft, it can be crumbled to a fine powder. It is an everyday reminder of the velocity of time on the earth—slow time, something built only to crumble, the same something she lived on. Moving dunes move with the wind, of course, and some are more precarious than others; pine trees help to stabilize the dunes and slow their strolls. The landscape around Allegan is a network of sand and shrubbery that has morphed into a kind of maze over time. There couldn’t be a better summary of her work since the 1972 purchase of the Allegan property: tender snapshots of time and movement that evoke nothing human or immediate, recalling the title of John McPhee’s profound book about geology—practical, philosophical, and, in a sense, theological—Annals of the Former World.

I arrive at John McPhee from two directions. The first is my grandmother, who kept a complete set of his books just to the left of a comfortable chair in her living room. She, like Statsinger, was a Jewish woman born in the 1920s. Pictures of the artist in the 1940s and 50s—her hair coifed short, her smile wide—remind me even more of my grandmother, who was born in Greensboro, North Carolina, and longed to live in New York. Born in Brooklyn as a somewhat frail child, Statsinger took yearly sojourns to the countryside with her family, leaving an indelible impression on her:

We used to go to the country once a year. And we’d leave at night, and I remember I thought I was going to the end of the world. It was dark, and I was sitting on somebody’s lap and, you know, eventually falling asleep, and in the morning, I woke up, and I could hear birds. And I went for a walk, and there was this pond. It was one of the most beautiful days, and the birds were singing, and the butterflies were flying, and all of the sky was very blue and so forth. And I remember thinking, here was—and the crickets were all around, and I remember thinking here was everybody. Everything was doing something, but what was I—what was it could I do? What was it I could do? And I solved it by saying, “I could think,” which really surprised me.[iii]

Maybe with Allegan the artist found a way back to a place where she could think, or maybe, as a kid raised in the city, she longed for the country.

Like so many other artistically inclined Jews of her generation, Statsinger attended the High School of Music and Art in Manhattan. After graduating in 1944 she did a six-month stint at the Art Students League of New York, then bounced to the University of Toledo for a year, during which she visited Chicago and was entranced by the painting collection at the Art Institute. She had a friend at the School of the Art Institute (SAIC) who wanted some company, so Statsinger sought admission and a year’s credit and graduated in 1949. After that—save a few years in Southern California, Mexico, Japan, Allegan, and some rather astonishing world travels—she made the city of her alma mater her home.

The young Statsinger found support from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in particular. As a juror for the 1950 edition of Exhibition Momentum, the architect was impressed by her work and recommended it to his students, some of whom made purchases, and to gallerist Katharine Kuh, who spread the word about the unusual young artist. Statsinger found a creative community among her fellow SAIC graduates and later still a community of artists and instructors including Leon Golub, Cosmo Campoli, Miyoko Ito, and Barbara Rossi.

She was also affected, as many were, by Kathleen Blackshear, who taught her students to not only look at art globally but also on the same register as artifacts of the natural world. Statsinger married Stanley Cohen, a theoretical physicist at the Institute for Nuclear Studies of the University of Chicago and later the US Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory, where he developed Speakeasy, an early and highly influential computer-programming language.

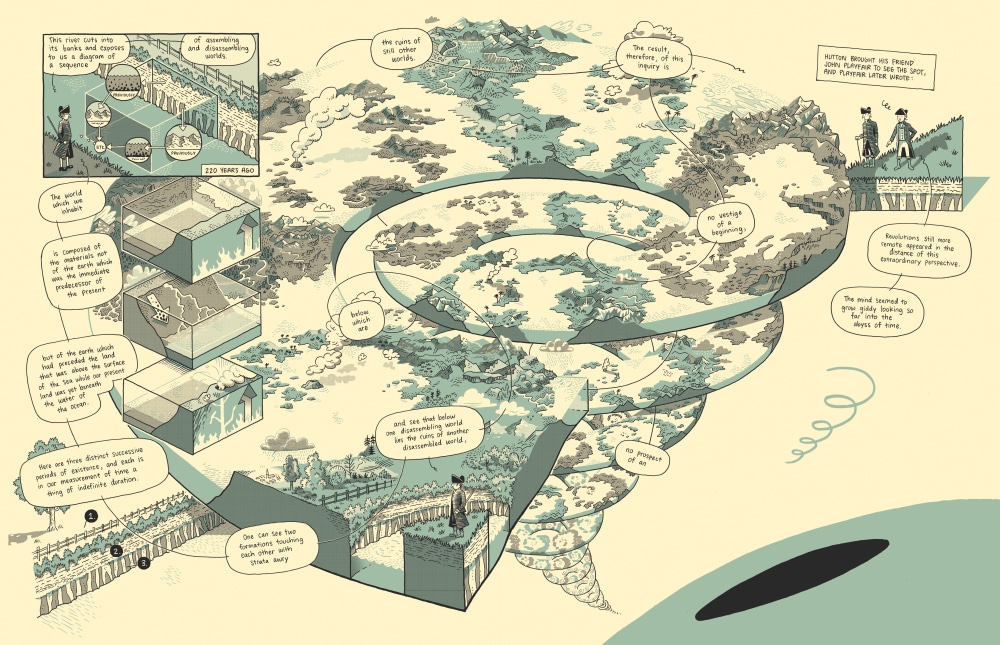

Kevin Huizenga, Glenn Ganges in: The River at Night (Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2019), 176–77.

My other path to John McPhee is through the Chicago-based cartoonist Kevin Huizenga, whose recent book The River at Night chronicles his longtime character Glenn Ganges’s mental wanderings in time and space during a single sleepless night. Like McPhee’s writing, Huizenga’s book is ostensibly about a single subject, but it drifts into and out of nearly all facets of waking life, if only for brief, insightful moments.

At one point the character Glenn Ganges reads a sign along Interstate 196 in Allegan County, a sign that the artist Kevin Huizenga passed on his frequent drives from Grand Rapids, where he attended college, to his family home in the southern suburbs of Chicago, forging an identity through patterns and land in the process. In the second half of The River at Night, Ganges reads Annals of the Former World, wherein McPhee focuses for a spell on James Hutton, an eighteenth-century medical doctor who is thought to have made the first geology-based claim that the earth might be more than five thousand years old. Indeed it took some personal might to proffer a beginning that did not begin as the Book of Genesis would have it. “Instead of attempting to imagine how the earth may have appeared at its vague and unobservable beginning,” McPhee writes, “Hutton thought about the earth as it was; and what he did permit his imagination to do was to work its way from the present moment backward and forward through time.”[iv] Hutton imagined the time it might take to form the earth, and on March 7, 1785, he read the resulting dissertation to the Royal Society:

"We find reason to conclude, 1st, That the land on which we rest is not simple and original, but that it is a composition, and had been formed by the operation of second causes. 2dly, That before the present land was made there had subsisted a world composed of sea and land, in which were tides and currents, with such operations at the bottom of the sea as now take place. And, Lastly, That while the present land was forming at the bottom of the ocean, the former land maintained plants and animals . . . in a similar manner as it is at present. Hence we are led to conclude that the greater part of our land, if not the whole, had been produced by operations natural to this globe; but that in order to make this land a permanent body resisting the operations of the waters two things had been required; 1st, The consolidation of masses formed by collections of loose or incoherent materials; 2dly, The elevation of those consolidated masses from the bottom of the sea, the place where they were collected, to the stations in which they now remain above the level of the ocean. . . .

A theory is thus formed with regard to a mineral system. In this system, hard and solid bodies are to be formed from soft bodies, from loose or incoherent materials, collected together at the bottom of the sea; and the bottom of the ocean is to be made to change its place . . . to be formed into land. . . .

Having thus ascertained a regular system in which the present land of the globe had been first formed at the bottom of the ocean and then raised above the surface of the sea, a question naturally occurs with regard to time; what had been the space of time necessary for accomplishing this great work? . . .

We shall be warranted in drawing the following conclusions; 1st, That it had required an indefinite space of time to have produced the land which now appears; 2dly, That an equal space had been employed upon the construction of that former land from whence the materials of the present came; Lastly, That there is presently laying at the bottom of the ocean the foundation of future land."[v]

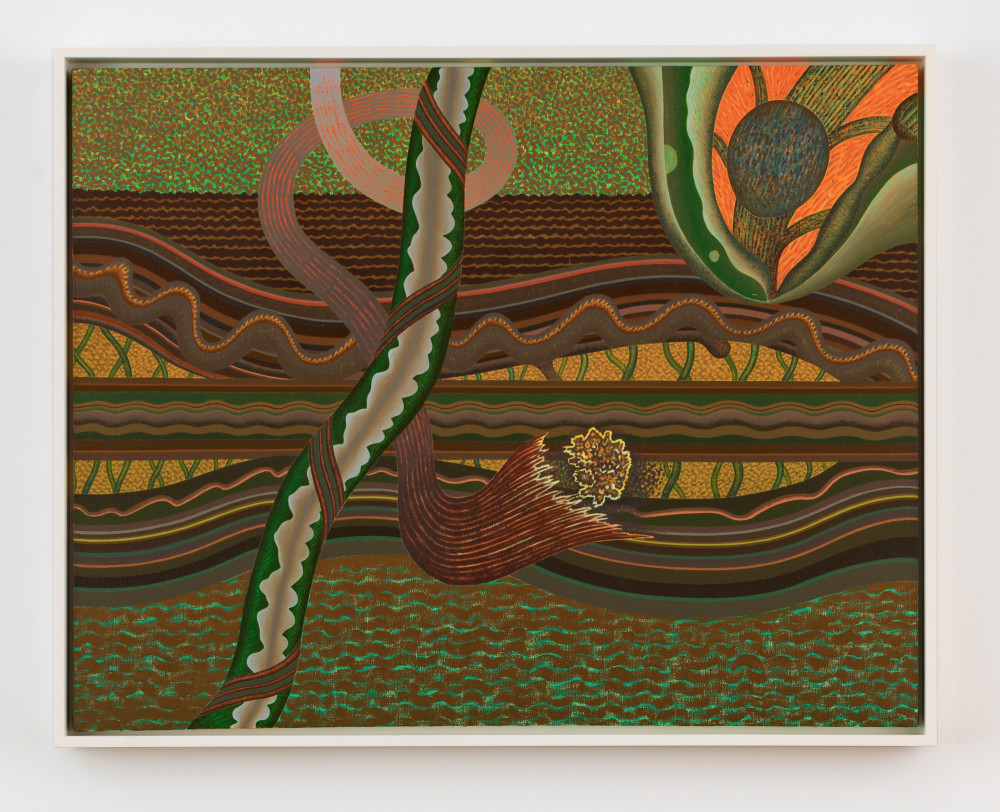

Shiftings, 1983

I wouldn’t have forced you to read all of the aforementioned if it wasn’t so strikingly like the experience of looking at artworks by Evelyn Statsinger—artworks with titles like Shiftings, 1983, Forest Gift, 1987, Cross Currents, 1985, Tidal Phases, 1984, and State of Flux, 1987. And it’s Huizenga, the Chicago-Michigan traveler, who led me here, not only adapting various and centuries-old notions of “time as space as spiral” for his own narrative purposes but also keying into the spiral’s status as the cartoon glyph for confusion. In scientific diagrams, however, the spiral offers clarity, representing the progression of both time and earth, and it just so happens to also look like a naturally occurring phenomenon. Indeed one of Statsinger’s most instantly recognizable forms is the spiral of a seashell, as in her divinity-like painting Shell Masks, 1975, and occupying center stage in Untitled, 1982. As artists, Huizenga may be more analytical and Statsinger more tactile, but—in addition sharing the land experience of Michigan—both share a sense of the big imagination, the time and space of our earth, and the patience to slow down, examine, and try to glimpse its complexity.

Another way to conceive of the movement of elements and time can be found in Lyonel Feininger’s September 23, 1906, installment of his comic strip Wee Willie Winkie’s World. Feininger depicts the movement of clouds over a quilted hill, each reacting to other in five sequential panels. Feininger contributed about a year’s worth of comics to the Sunday edition of the Chicago Tribune, which at the time was trying to make customers of the city’s enormous German population. Walter Gropius eventually recruited Feininger for the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany, in 1919, where the artist taught until 1925. Together with Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky, and Paul Klee, Feininger formed the Die Blaue Vier (The Blue Four) in 1924. He surely would have also crossed paths at some point with Mies van der Rohe, who went on to be the school’s final director. Which is all to say, it’s a small world.

Shell Masks, 1975

Statsinger usually worked directly on her supports without any planning. In a rare letter from 1980 she describes the process behind a series of twelve paintings created between 1973 and 1975, a series that includes Shell Masks:

This is the first time I used sketches as a basis for the composition. Although my work looks planned I generally prefer working directly without sketches keeping all the intricate balances in motion until the end. In this way I hope to keep a freshness of vision and allow openings for new thoughts to enter—thoughts that are the children of the working process itself. However these 12 paintings were a kind of discipline and the original simple line drawing was projected on the canvas keeping the central figure as a fixed point in continual juxtaposition against the background. It is a kind of ever present figure of menace against a tranquil natural background—a duality of man-made and natural things.[vii]

“Menace against a tranquil natural background” could mean many things. One of them might be the East Asian autumn olive trees that she planted, which are known for their dual-colored leaves and invasive growth. Another might be the looming threat of nuclear destruction that hatched, in part, in the program that became the Argonne National Laboratory. Still another could be a couple of city slickers—Evelyn still with a detectable Jewish-Brooklyn accent—erecting their fortress on what used to be underwater.

When Statsinger writes elsewhere that the title of her work Random Paths is “a metaphor for the life of the mind, a kind of strolling through the actual present landscape, as well as remembered landscapes,” such a statement could be taken as a Surrealist prompt. And she did indeed like Surrealism—Chicago was practically suffused with it, after all. It is ultimately neither the Europeans nor their local descendants to whom Statsinger is most aligned, however. When one imagines a painter of nameable things in Chicago, she is closer to, say, the process-oriented pictures of apprehension by Terry Winters; the post-1960s organism-oriented Lee Bontecou; or, to take a more contemporary example, Edie Fake’s desert-scape paintings (and of course there are the emotive, biomorphic abstractions of the aforementioned Miyoko Ito). And she is closest of all, I’d argue, to what Hutton imagined, McPhee wrote, and Huizenga drew: a walk through the present landscape to find the different terrains, time zones, and views.

One of Lyonel Feininger’s esteemed cohorts, Paul Klee, was influential on Statsinger’s early work. This is not to ignore the influence of the spindly line–based vernacular of everyone from William Steig to Ben Shahn to Andy Warhol, but it is Klee’s simple 1931 watercolor in the collection of the Art Institute, Blooming Plant, that brings him immediately to mind. This painting is finely observed and rendered, but with a speedy hand that promises future revelations. It is undeniably the work of an artist’s labor—a charcoal bed on which there is a cluster of blood-orange dots, tiny hatch marks alongside thicker brush strokes, and confident corners, all of which give way to gentle fading and, finally, an explosion of red pigment. It is just specific enough to bring us in, and just strange and eventful enough to mystify. All in service to an evocation of life.

Statsinger, like Klee, had an arsenal of ways of touching to animate her art. She worked on two or three objects at a time, and while drawing she often divided a sheet of paper into quadrants before delineating forms in earnest.

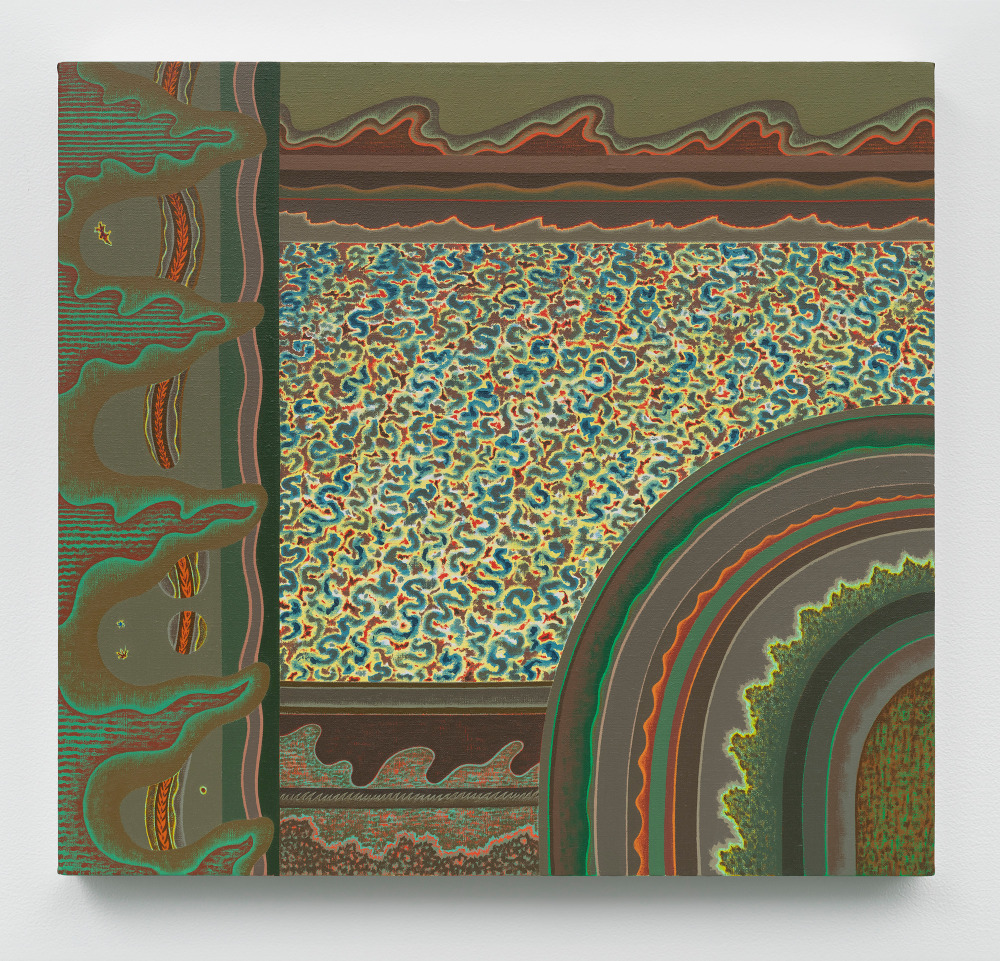

Central Forces, 1985

But that was about all of the planning she did, and certain spontaneous “events” are hard not to see: an expulsion of tone from a coiled form (almost a spiral) in Conflagrations, 1983; an ocean of acidic amoebae in Central Forces, 1985; shifting macro- and micro-views of tongue-like fronds in Tidal Phases, 1984, as though seen through a scope is in motion; and Crosscurrents, 1985, which offers a sectional view of the layers of the earth and a fallopian tube ejecting a mass to nowhere. It’s not such a stretch to imagine walking upon a surface and concocting these depths. Statsinger loved walks around her garden, the acres of her property, a nearby preserve, and, a short drive away, the Lake Michigan shore. The woods—which must have crunched underfoot and shocked the senses with a sharp pine smell—appear in Forest Gift, 1987, whose orange portal, investigated by a red stamen, makes this work as close to an erotic painting as Statsinger would ever get.

Cross Currents, 1985

The artist Suellen Rocca remembered that walking on the beach with her could be excruciating; Statsinger kept her eyes on each rock almost interminably, focused on extracting any and all visual information.[viii] She collected seed pods, shells, twigs, leaves, and stones, which she arranged carefully in her studio. She could go macro or micro with these specimens—making them a subject or finding new details within them. According to her friend Julia Fish, Statsinger’s working method was similarly organic. She accepted every mark and built on it. She didn’t remove anything, and she didn’t subtract. She would instead “fix” mistakes by adding something adjacent to them.[ix]

This process meant that Statsinger would find an image by arraying her vocabulary of marks and forms—tonal clouds, buttercups, threads, stems, fossils, shells, husks, ripples—but never in a way that any of these things become individually identifiable. Instead they interlock and accrete with the texture of graphite on paper or oil on canvas. This accumulation vibrates like the sway of pine trees, pleasantly and perceptibly altering one’s view. The motion is meditative, and the drawings ask of the viewer the same absolute and unwavering focus that the artist gave a rock on a beach. Because of her precision the images are crisp but remain ambiguous. They are pictures of something, that is. Perhaps they are what guides us into the spiral, the sensation of ever-present time and matter. But Statsinger was not an image maker per se. She was sui generis and focused—perhaps most of all, once she’s walked and imagined—on touch. Touch rocks, touch shells, touch paper, touch canvas. It’s touch that brings me back and allows us all to enter that “state of grace” she so loved.

For Suellen Rocca and Karl Wirsum, with gratitude.

D.N.

Statsinger watering her yard in Allegan, Michigan, 1979

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY

Evelyn Statsinger (1927-2016) was born in Brooklyn, New York, and lived and worked in Chicago. While in New York, Statsinger studied at the Art Students League. Relocating to Chicago in the 1940s, she worked at the University of Chicago and went on to receive her degree from the School of the Art Institute in 1949.

Statsinger depicted her experiences of the natural world through drawing, painting, and sculpture. Her early drawings, characterized by their clean lines and all-over patterns, drew the interest of luminary artists and museum curators, including IIT Director Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe and Art Institute of Chicago curators Katharine Kuh and Carl Schniewind, and led to solo exhibitions at the Art Institute in 1952 and 1957.

Statsinger photographing her shadow, 1979

She was frequently included in discussions of the Monster Roster school of Chicago artists because of the distorted figures present in her early work, as well as the later, broader conversation around Chicago Imagism. Throughout her life, however, Statsinger made work that was profoundly individual and fiercely independent. In her mature work, she abandoned recognizable or figural forms in favor of fantastical visions abstracted from nature. Statsinger worked across a variety of media creating complex psychological and colorful compositions that balance abstraction, representation, and fantasy.

PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, Illinois

Elmhurst University Art Collection, Elmhurst, Illinois

Illinois State Museum, Springfield, Illinois

Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois

Museum of Graphic Art, New York, New York

National Art Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Richland Community College, Decatur, Illinois

Rockford Art Museum, Rockford, Illinois

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York

Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts

Dan Nadel at Gray New York, 2022

Dan Nadel is the Curator at Large for the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at the University of California, Davis, where he has organized exhibitions on Kathy Butterly, Mary Heilmann, and William T. Wiley. Nadel is the editor of several books, including Peter Saul: Professional Artist Correspondence; The Collected Hairy Who Publications, 1966–1969; and It’s Life as I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940–1980. He has also curated exhibitions including What Nerve! Alternative Figures in American Art: 1960 to the Present; Suellen Rocca: Bare Shouldered Beauty; Gertrude Abercrombie; and, most recently, Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Nadel, a 2021–2022 Fellow at the Leon Levy Center for Biography at the Graduate Center, CUNY, is currently at work on the biography of underground comic artist Robert Crumb (Scribner, 2024).

i. Evelyn Statsinger, Statement, Jan Cicero Gallery, Chicago, Illinois, January 11, 1991. Evelyn Statsinger Cohen Trust Archives.

ii. Evelyn Statsinger, “Oral History Interview with Evelyn Statsinger,” interview by Lanny Silverman, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, May 11–13, 2005. Link.

iii. Ibid.

iv. John McPhee, Annals of the Former World (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1998), 72.

v. James Hutton, Abstract of a Dissertation Read in the Royal Society of Edinburgh, upon the Seventh of March, and Fourth of April, M,DCC,LXXXV, concerning the System of the Earth, its Duration, and Stability, 1795, quoted in McPhee, Annals, 75–76.

vi. Kevin Huizenga, The Riverside Companion 1, July 2019, 9.

vii. Evelyn Statsinger to Harry Rand, March 25, 1980. Evelyn Statsinger Cohen Trust Archives.

viii. Suellen Rocca, conversation with curator and art historian Daniel Schulman, January 2022.

ix. Julia Fish, conversation with the author, January 2022.

Unless otherwise noted, all archival photographs courtesy The Stanley and Evelyn Statsinger Cohen Foundation Archives.